- Home

- M. A Wallace

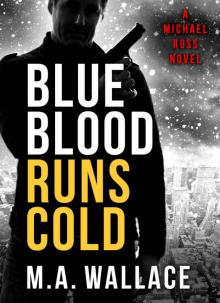

BLUE BLOOD RUNS COLD (A Michael Ross Novel Book 1)

BLUE BLOOD RUNS COLD (A Michael Ross Novel Book 1) Read online

Blue Blood Runs Cold

A Michael Ross Novel

M. A. W A L L A C E

MICHAEL ROSS NOVELS

Blue Blood Runs Cold

Fire In The Heart

Women of the Night

Christmas Murder

The Last Bullet

Copyright © 2015

All Rights Reserved.

This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, contact the publisher at [email protected]

This is a work of fiction. All characters appearing in this work are products of the author's imagination. Any resemblance to events, businesses, companies, institutions, and real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Table of Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter One

1

The town of Shippensburg, Pennsylvania had three patterns of weather during the fall and spring college semesters: cold, windy, and rainy. The college semester began after Labor Day in September, when the summer heat began winding itself down. Students had less than a month to enjoy fair weather before the cold began to creep in. Freshmen who came to the university—forced both to live on campus and take a meal plan—gained weight eating food at the dining hall buffet. Juniors and seniors had been around long enough to know about the gym, where it was and what they needed to do to use it. They managed to work off the “freshman fifteen,” and perhaps a bit more. From December to March, the administrators of Shippensburg University noticed a drop-off in gym usage compared to other months. Fewer people exercised when they were forced to brave the cold by walking across campus; there were no parking spots available next to the gym, save for those reserved for the Luhrs Center for Performing Arts, a place where third-rate musicians, second-rate comedians, and lecture circuit junkies came to ply their various trades.

Like many universities, the parking situation at Shippensburg became increasingly untenable as the years went by. Most of the students at Shippensburg commuted either from their own apartments in town or from out of town where they lived with family or friends. The campus housing, which provided no air conditioning, little heat in the winter, and the constant racket of students acting up through all hours of the night, drove people away to live off-campus. The living situation for students living off-campus was only a little better in privately owned apartment complexes. There were still drunken parties, gay slurs thrown about everywhere, and noise and confusion while others tried to sleep, study, or prepare for work. The difference between the two lay in the amenities: apartments offered heating and air conditioning, together with the option of keeping pets.

Those who were able to find work counted themselves lucky. The last census reported Shippensburg as having 5,500 people, while Shippensburg University claimed 2,625 residents. There were not 2,625 jobs to be had in the town, much less in the surrounding area—most of which was farm country. Freshmen got the first pick at all the jobs on campus, leaving transfer students unemployed. The only way they could survive at school was through student loans, and, in some cases, through assistance from local food banks.

Though the president and vice president of student affairs held biweekly meetings in the basements of various dorms, less then forty people out of the seven thousand of the student body attended those meetings held at nine o'clock at night. For commuting students, the chance to speak up before the ultimate authority on campus was entirely out of the question. Still more people who heard about the meetings chose not to go—either because they were focused on their studies or because they did not believe that any positive change made would directly affect them. The changes which had come to the campus had been the gym and the new housing dorms, both of which had been built over the course of three semesters. The seniors who were at the university for each improvement never got the chance to enjoy the new buildings that their tuition had helped pay for. This, together with construction occurring at seven in the morning, loud and blaring, made Shippensburg a miserable place to attend classes.

The fall semester of 2015 had gone on as every other fall semester had. There were long lines outside the door of the financial aid office as students wrangled with a broken, inefficient federal system. The few student clubs that did exist saw their open house meetings have incredible attendance, which invariably tapered off until only a handful of people were left at the end of the semester. Multicultural events were held, many of which were only attended by resident life staff and those who wished to eat what free food they could. The Women's Center, with its two staff members, one intern, and two volunteers, was everywhere doing everything. The pride they took in accomplishing their goals was balanced by the stress they took on as a result of doing extra tasks, many of which had no tangible reward.

The school's newspaper and television station, both run by students who didn't yet know what they were doing, often failed to shine a light on the various issues students went through. When an article appeared that did address the various problems on campus, it was often written poorly or edited poorly, or both. Students were stressed, often without relief. By and large, they accepted their stress as a fact of life, intending one day to leave or transfer out of the university. The buildup of personal strain on individuals found release in a high non-completion rate. The rate of students who did not complete a four-year course of study was determined by the number of students who flunked out of school, who transferred out of school, and who dropped out of school. Though the problem was kept as carefully hidden as possible, it became readily apparent to the students who did get their degrees that there was a revolving door at the university: people came in, people went out.

Over the years, this had been enough to keep the pressure building up over time from boiling over until the budget cuts to Pennsylvania's state system of schools, called PASSHE, of which Shippensburg University was a part, came into effect in the middle of August. Suddenly, introductory psychology courses, still a requirement for most majors, packed one hundred students in a single classroom with one instructor. The art and language department, both of which had already been under-funded and under-represented, had been put into an even more precarious position. The anthropology department, which had consisted of three people, was eliminated altogether. The available gym time was limited. Where it had once opened at seven in the morning and stayed open until eleven at night, it now operated from ten in the morning until four in the afternoon.

Additionally, the budget had been mismanaged by the new interim president. The previous president had left, seeing the writing on the wall. This led to an unexpected release of six instructors, two of whom had tenure. Classes that students thought they'd had at the beginning of the semester had to be rearranged. The chaos on the opening week of the fall semester was beyond reckoning. Even so, with everything that had gone wrong, with all the problems and adjustments, the students at Shippensburg still bore with it, making their plans to leave the university as soon as they could.

That was, until December came. Early snows came late in November—so much snow over the course of two weeks that by the beginning of December, tensions were at a breaking point. The university took snow days at first, but then could not take any more, as finals and the end-of-semester projects that accompanied them were close at hand. Those commuters that did

come to school, even while the same budget-cutting governor refused to declare a state of emergency, chalked it up as one more reason to hate the university that colloquially called itself Ship.

On December second, an accumulation of heavy snowfall combined with slightly above-freezing temperatures caused the snow to gain weight as it turned slowly to a liquid form. The weight proved too much for the university's oldest dorm, Ravney Hall. The roof caved in in three places at seven o'clock in the morning while students who dreamed of better situations slept in their beds.

The snow had also collapsed into the stairwell—a problem which made assessing the situation difficult for the maintenance crews who arrived at 8:10, over an hour after the roof caved in. They found mucky slush in the stairwell, and a hallway at the end of which sat a large puddle where the snow had fallen directly next to a heater. The stone floor did not permit the water to leak through to the ceiling below it. Instead, it spread out into a large puddle that snuck underneath the doors of two rooms, causing no small alarm for the residents of those rooms.

Buried beneath a pile of solid white, they also found Jolanda Price's dead body.

Jolanda was a resident assistant who became an unfortunate victim of the weather. A heavy pile of snow had fallen down onto her bed, smothering her. She awoke in a panic, and, because she had asthma issues that required an inhaler, began hyperventilating. She died of suffocation shortly afterward.

When the workers dug her out, they knew that they were looking at a very problematic situation. They knew that the administrators tip-toed around, both in making rules and in enforcing them, so as not to upset the parents of the children who endured Shippensburg. They all had known Jolanda, for she had been known everywhere on campus. She had been omnipresent. Her smiling face and easy laugh made her friends with the students and faculty. She was black, which they knew would further complicate the problem. It was not so long ago that black students at Shippensburg had to endure the virulent racial hatred of a backwards community which clung to the past.

A ray of sunlight shone on her face while she lay motionless in bed. Even her shocked, panicked expression took on a strange radiance that was remarked upon afterward by anyone who ever told the story of her death. She had been nineteen years old.

2

The interim president was Lorraine Clifton, who sometimes liked to be called Dr. Lorraine. By nine o'clock, put her face in her hands. She wanted to weep, but there were no tears. She wanted to tear her hair out, but she stopped herself when she considered that she might be looking for a job over the winter break. She would need to look as presentable as possible. On top of severe cutbacks to a university that had built a gym and new residence halls, she had to deal with complaints from students of all kinds. Every petty thing that went wrong, from a leaky water fountain to bad food in the dining hall, was placed on her shoulders. During her biweekly town hall meetings, she had given up the idea of speaking her mind about what changes the university would make for the spring semester to recover from a disastrous fall. She had simply listened to all the students, one after another, tell her their grievances.

The vice president of student affairs was a middle-aged, overweight man named Oliver Newton, who looked as harried as she felt. She hid her distress better than he did; she did not let sweat form so quickly and so often on her brow that she had to wipe it every five minutes, for she made a point of drinking ice-cold water to lower her body temperature during the town hall meetings. She did not glance about this way and that, looking for an answer but finding none, saying with perfect confidence the phrases of polite dismissal that meant nothing. She sat in silence. She listened. She felt speaking would only make matters worse.

Now, a girl had died. That, perhaps, was not the worst problem. The third floor of Ravney Hall would have to be closed off until sufficient repairs could be made to the roof. Where would the students living on that floor go? There were other rooms available in other dorms, left empty by students who had started out assigned to a space but who had moved out within a week when they found a roommate not to their liking. That had always been the case no matter what college she worked for or visited. Blind draws and assigned quarters always led to interpersonal conflicts. Moving people who had become comfortable in their rooms to another new location would only give the students more reason to complain. If there ever was an atmosphere ripe for a student strike, she thought, this was it.

Her predecessor had always dealt with problems immediately. As soon as they came to his attention, he attempted to rectify the situation at once. She had always thought that a special conceit of his, trying to substitute responsiveness for efficiency. The truth was, in a heavily bureaucratic college in which the school's legal counsel held a great deal of influence through the board of trustees, problems could not always be resolved easily or quickly. This was especially true of a residence hall with a collapsed roof and a student found dead in her bed.

Her watch read 8:37 by the time she walked out of her office and out into the small lobby where her secretary typed away at a keyboard, oblivious and unaware. Lorraine grabbed a piece of candy out of a candy jar sitting on the woman's desk and put it in her mouth. It was the best thing she could do for the moment, since she couldn't have a cigarette. She desperately craved tobacco as she had not before in the seven months since she quit smoking. She had congratulated herself on working through all the troubles the university experienced without even having a craving. At the moment, standing in her uncomfortable blue flats, she wasn't sure if she would give in this time or not. Surety had blown away on the gusts of cold air that always came to Pennsylvania in the winter.

She said to her secretary, “Excuse me, Corrine.”

The woman, who was sixty-seven years old with withered fingers, white hair, and a thick pair of bifocals, said with a sure, commanding voice, “Yes, Miss Clifton?”

Though Lorraine had been divorced for three years, she still found it jarring to hear herself addressed as “miss” instead of “missus.” There were days when she could not believe that so much time had passed since she had divorced her husband after he had joined a Christian cult. He had begged her to join him, but that would have meant leaving her administrative career. At the time, she had only been an assistant director of housing at Lock Haven University, but she had her sights set higher. She had wanted more out of life than answering phone calls and being at someone's beck and call. She had wanted to be the one in charge, the one who made the decisions. After her divorce, she had gotten exactly what she had wished for.

She said, “Clear my schedule for the day. A student has died. I want to see all the administrative staff and the board of trustees together all at once.”

The secretary's eyes widened. She said, “All of them? As in, all of them?”

“All of them. As soon as possible. As in, five minutes ago. Tell them to meet me down in Shanks. It's the only place large enough to hold everyone.”

As she headed out of her third-floor office in the oldest building on campus, she tried to think of what she would say to all those people. She knew that some of them wouldn't come. Those who didn't, she thought, might not have a job after the semester. But then, as she began descending the stairs to the employee cafeteria, she wondered if anybody in the university would have a job come January.

3

Though the residents on the third floor of Ravney Hall had all been woken up by the roof collapsing, no one thought to look in on Jolanda. It was known throughout the building that she made a habit of getting up early, even on Fridays. She had an 8 a.m. chemistry class. Prior to that, she often showed up outside the doors of the dining hall, waiting for it to open at seven so she could be the first to eat chocolate chip pancakes. No one thought it suspicious when she didn't answer her door. The blinds over her window had always been closed, preventing anyone from looking in. She did not answer her cell phone, which was also not unusual for her, as she never took calls or responded to messages until noon. Her friends

had always told her that she should be more attentive to her phone; she had always ignored their advice. There were simply too many calls and too many messages to cope with. Jolanda answered only her three closest friends regularly, and got to the rest whenever she felt like it, which wasn't often. She was not a phone person.

Consequently, the maintenance workers discovered her body first. Then, as students came out of their rooms to see what the matter was, they saw Jolanda's body.

The students at Shippensburg University used a smartphone app that allowed people to post messages anonymously on a board that everyone in the area could see. For the majority of the fall semester, the students had used it to complain about conditions at Ship. They had invented derogatory hashtags to make fun of the university, the administrators, and the food. No one and nothing was spared from their criticism. The app became more popular on campus than any other social media site, for it was only way that people could hear authentic voices speaking out on a daily basis.

The voice that spoke out at 8:32 a.m. belonged to Matthew Fullminster. Matthew was a sophomore who had already been accepted as a transfer to Penn State for the spring semester. He took his cell phone out of his pocket, connected to the dorm's weak Wi-Fi signal, and typed in his message: Jolanda is dead. Roof collapsed. Buried under snow.

Within five minutes, everyone who used the app at that time of morning knew what had happened. With knowledge, came anger. With anger came the will to take matters into their own hands. It began with a support group called To Write Love on Her Arms, where people could let out all their private hurts and talk about their suffering. There were often cathartic experiences in the group, as young girls just out of high school talked about having been sexually assaulted. A senior getting ready to graduate in the spring often spoke of his sister, who had been on and off a suicide watch for a year while she was in and out of mental institutions, most of which kept her for sixty days then released her. The members of the group who lived on campus, even those who had not regularly attended, gathered for an impromptu meeting at 8:45. Tears were shed, stories were told, classes were forgotten.

BLUE BLOOD RUNS COLD (A Michael Ross Novel Book 1)

BLUE BLOOD RUNS COLD (A Michael Ross Novel Book 1)